The Cook County Land Bank is chipping away at abandoned properties one house at a time

By Maya Dukmasova | August 12th, 2016

Imagine a county agency that doesn’t rely on taxpayer dollars to operate. And not only that, but it also generates wealth and helps revitalize struggling neighborhoods.

It’s not a fairytale, but how boosters describe the successes of the Cook County Land Bank Authority, now in its third year of operating.

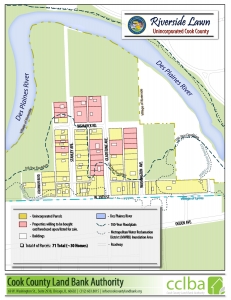

The land bank’s purpose is twofold: to buy and resell abandoned property for rehab or redevelopment, and to clear land of blighted structures and revert it to redevelopment or community uses like parks and gardens. And since it’s inception in 2013, the land bank has acquired 335 properties in Chicago and suburban Cook County—mostly blighted, abandoned homes, but also vacant lots, commercial buildings, and industrial sites—in an effort to reverse the devastation of the foreclosure crisis and resulting population loss.

The land bank’s purpose is twofold: to buy and resell abandoned property for rehab or redevelopment, and to clear land of blighted structures and revert it to redevelopment or community uses like parks and gardens. And since it’s inception in 2013, the land bank has acquired 335 properties in Chicago and suburban Cook County—mostly blighted, abandoned homes, but also vacant lots, commercial buildings, and industrial sites—in an effort to reverse the devastation of the foreclosure crisis and resulting population loss.

Of those 335 properties—which the land bank mostly acquires through donations from banks and individuals—190 have been sold to developers for rehab. Of those, nine have then been resold to new owners.

This may not seem like a lot, but the land bank began acquiring properties two years ago with just a $4.5 million grant and a landscape of more than 51,000 abandoned addresses throughout the county—one main result of the subprime mortgage crisis.

The land bank has the authority to acquire abandoned properties tied up in foreclosure proceedings or weighed down with back taxes and other fines, wipe their financial slates clean, then sit on them them until an interested buyer comes along.

Click here for the complete article posted on the Chicago Reader’s website! All of this is possible by a terrific network of partners committed to making serious and positive change in our communities!

Rob Rose Selected as Member of Leadership Greater Chicago (LGC) 2017 Class of Fellows

Leadership Greater Chicago (LGC) announced today the 2017 Class of LGC Fellows. This select group of 38 accomplished and diverse individuals represents a cross-section of professionals from the corporate, nonprofit, government, and education sectors. They share the goal of effecting real change in the community. | July 20th, 2016

Leadership Greater Chicago (LGC) announced today the 2017 Class of LGC Fellows, which includes our very own Executive Director Rob Rose!. This select group of 38 accomplished and diverse individuals represents a cross-section of professionals from the corporate, nonprofit, government, and education sectors. They share the goal of effecting real change in the community.

Selected from more than 120 highly qualified candidates nominated by their employers, the Fellows will engage in a 10-month program where they will be immersed in key socioeconomic issues facing our city and the region, including education, economic development, healthcare, housing and infrastructure, criminal justice, and race. Additionally, the Fellows will have an opportunity to engage in small group projects of their choice to directly address a challenge or need in the community. These projects will be informed by the information and ideas shared in the classroom, engagement with other Fellows, and personal experiences.

Fellows selected for Chicago’s premiere program for developing civic leaders have demonstrated remarkable professional achievement early in their careers, a commitment to their community, and the potential to influence effective change.

The 2017 Fellows advanced through a highly competitive selection process, including a comprehensive written application and interviews with graduates of the LGC Fellows Program. The LGC Board of Directors approved the selection of this year’s class.

“The LGC Fellows Program is rooted in the belief that a small, diverse group of committed leaders can change the world,” said Maria Wynne, Chief Executive Officer of Leadership Greater Chicago. “The hallmarks of our program are access to world class thought leaders, priceless community experiences, and the peer learning and friendships that take shape among the Class. The personal connections and sense of responsibility with which they emerge drive their lifelong commitment to effect real change in the region.”

Click here for the complete list of Leadership Greater Chicago’s 2017 Fellows.

CCLBA Turns to DAWGS to Secure Their Properties

The Cook County Land Bank Authority consulted with the security experts at Door & Window Guard systems (DAWGS) to secure their vacant properties. | February 9th, 2016

The Cook County Land Bank Authority (CCLBA) was formed to stabilize blighted neighborhoods and stimulate redevelopment and return properties to productive use. The CCLBA also promotes economic development by generating jobs and providing affordable housing.

The CCLBA deals with a host of asset management issues as it holds vacant properties. Lock boxes often go missing or keys are not returned. Front doors can be compromised resulting in break-ins. These issues slow down the process of getting properties into the hands of qualified investors and homeowners.

The CCLBA deals with a host of asset management issues as it holds vacant properties. Lock boxes often go missing or keys are not returned. Front doors can be compromised resulting in break-ins. These issues slow down the process of getting properties into the hands of qualified investors and homeowners.

The CCLBA took a proactive approach and consulted with the security experts at Door and Window Guard systems (DAWGS). DAWGS listened to the concerns of the CCLBA and created a customized solution to alleviate the problems associated with missing lock boxes and keys. DAWGS installed their proprietary coded steel doors on CCLBA properties which allowed the CCLBA to control access to the properties without compromising the security.

“We made the decision to partner with DAWGS because they offered a solution to a serious, ongoing problem”, says Robert Rose, Executive Director of CCLBA. “Now that we are working with DAWGS, we no longer have these challenges; we are able to get vacant properties back to the community quicker, more efficiently and with fewer concerns on security.”

DAWGS steel door and window guards keep the CCBLA properties safe and secure from break-in. The coded door guards provide managed access to the property – without the hassles of keys or lock-boxes. The land bank can manage who enters the property and the contractors can feel secure and comfortable leaving their tools and equipment in the property. DAWGS is proud to support the mission of the CCLBA and is now the exclusive provider of vacant property security for the Cook County Land Bank Authority.

ABOUT CCLBA

The Cook County Land Bank Authority was formed in 2013 to address the growing inventory of vacant residential and commercial properties in Cook County, Illinois. The Cook County Land Bank Authority (CCLBA) is the largest land bank by geography in the United States – their mission is to acquire vacant property, hold it and then transfer the ownership of property throughout the county. This promotes redevelopment and reuse of vacant properties. Learn More

ABOUT DOOR AND WINDOW GUARD SYSTEMS

DAWGS (Door And Window Guard Systems) is a full service vacant property security company. Our flexible, fast-response teams install and remove DAWGS equipment to ensure that your property is always secure. DAWGS currently has operations in Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Washington, D.C. and will be expanding into other new markets soon.

‘Zombie’ homes give Chicago operators an opportunity

By Dan Weissman

In early July, Chicago police officers arrested four men for taking over 14 vacant foreclosed homes — living in some and renting out the rest — mostly in prosperous neighborhoods. Seven years after the housing market crashed, there are still enough vacant homes to provide opportunities for this kind of creativity.Eight of the houses were in Beverly Hills and Morgan Park— South Side Chicago neighborhoods that look like suburbs, complete with big brick houses, winding streets and a vigilant neighborhood group, the Beverly Area Planning Association.

One of the homes sits a block and a half from the group’s office, on a street the association’s executive director, Margot Holland, describes as “beautiful,” lined with trees and spacious houses.

One of the homes sits a block and a half from the group’s office, on a street the association’s executive director, Margot Holland, describes as “beautiful,” lined with trees and spacious houses.

The taken-over house fits right in. The white-brick split-level is obviously well cared for, with tidy landscaping and a sign in front indicating that a security system is in place. “Yeah, it definitely doesn’t look suspicious,” Holland says.

So, how does a tidy home on a beautiful block end up ripe for the picking?

For help in understanding the context and in sorting through the public records, I turned to Rob Rose, director of the Cook County Land Bank Authority. Created in 2013 to help clear a backlog of vacant foreclosed properties, the land bank focuses on a collection of 23,000 tax-delinquent parcels.

Asked how long it might take him to dispose of all 23,000, Rose has a ready answer: “The rest of my life.”

His answer is based on a simple calculation. Rose thinks that clearing 500 properties a year — by finding new buyers or recommending targeted demolition — would be a pretty good pace for his small office. At age 44, that would keep him in the job until he’s 90.

However, as a public records search on the taken-over homes shows, there are far more than 23,000 vacant properties.

None of the eight properties in Beverly and Morgan Park are on Rose’s lists, because the property taxes are still being paid, presumably by the lender, as a hedge against forfeiting the parcel in a tax auction.

“This is the most difficult type of property to get to, because there’s no immediate red flags,” Rose says.

For the split-level, records show foreclosure started three years ago, but the lender hasn’t taken title. That’s about average in Illinois, which has more protections for homeowners than many states.

According to Daren Blomquist, vice president of the real-estate analytics company RealtyTrac, that delay means a foreclosed home in Illinois is more likely to be abandoned. “The longer it’s in that process, the better the chance that the homeowner is just leaving the property.”

Nationally, RealtyTrac counts about 127 thousand of these “zombie properties” stuck in foreclosure indefinitely. “When you consider that at any given time, there’s probably a couple million homes for sale, this isn’t an overwhelming number of properties,” Blomquist says. “Compared to overall inventory nationally, it really is a drop in the bucket. I think this really is a neighborhood issue.”

But even in a nice neighborhood, a few zombies here and there can provide an opening for creative operators.

Cook County’s Land Bank is betting on Austin

By Michael Romain

When, earlier this month, the Cook County Land Bank Authority identified 13 Chicago neighborhoods and 13 surrounding suburbs in which to aggressively purchase vacant single-family and multifamily properties — Austin was on the list.

The selected areas all have a concentrated supply of what the Woodstock Institute — a Chicago-based research and financial  advocacy organization — calls “zombie properties.” Those are properties in which a foreclosure case “has been filed but not resolved for more than three years.”

advocacy organization — calls “zombie properties.” Those are properties in which a foreclosure case “has been filed but not resolved for more than three years.”

“Because neither the borrower nor the servicer has clear control of the property, neither has a strong incentive to assume responsibility for the property,” the report notes. “Zombie properties, therefore, are likely to be poorly maintained or blighted, which threatens the stability of surrounding communities.”

In its 2014 report, the Woodstock Institute reported nearly 6,000 zombie properties in Chicago. Most of those homes, the report notes, are “disproportionately concentrated in lower-income communities” and “are more likely to occur in racially homogenous communities.” More than 250 of those properties, or about 12 out of every 1,000 mortgageable properties, were in Austin.

The land bank will work to revitalize those “zombie properties” and prevent other vacant properties from deteriorating into zombies by purchasing the properties, establishing site control and holding them for potential developers.

“What we do is come in … and write off those back taxes and work with

[municipalities] around those code violations, so when we convey the property to a developer, at a minimum, what he knows is [he’s] got a tax-free, lien-free property that has been secured, cleaned out and maintained,” said Rob Rose, the land bank’s new executive director, during a recent informational meeting on the bank in suburban Maywood. Rose has also presented in Austin before the West Side NAACP.

“What the developer has to worry about now is just the cost of bringing [the property] back on line,” he said. “He doesn’t have those other unknowns that he’d have if he was just trying to do it by himself.”

Rose has noted that the 13 neighborhoods that the land bank has chosen to target not only have a concentrated supply of distressed properties, but also the potential to attract a sufficient supply of interested developers and end-users. The neighborhoods that were excluded, such as Englewood, North and South Lawndale and West Ridge, wouldn’t receive special attention because “there is too much to overcome,” Rose told the Tribune this month.

Rose is cautious and perhaps necessarily so (the land bank is only funded to the tune of $4.8 million); but his community-wide approach is nonetheless much more ambitious and less discriminating than that of his predecessor, Brian White.

Whereas White’s decision to buy and hold hinged on the future marketability of individual properties, Rose is betting on whole communities. It’s a process that requires a much broader array of stakeholder conversations — not just those among business, real estate and government professionals.

In Austin, the land bank is in talks with the West Side NAACP to craft a community benefits agreement. The agreement, “at its core,” establishes the aims and goals the community envisions for the development process, Rose said.

“It can be very specific, in terms of the number of jobs and businesses or it can be more general. I prefer to have it more general in scope, only because these opportunities are very dynamic and its very hard to nail down hard set numbers on this. But the spirit of it is what you want to agree to. We want to have community participation and make sure that the needs of local businesses are addressed in that benefit agreement,” he said.

The difficulty in this approach, Rose noted, is how precisely that community-wide consensus comes about. And a lot will be riding on the outcome. Rose said that what the land bank is trying to do in Austin “is going to serve as a model of how we’re going to engage other communities in the county.”

“I want to see how well the NAACP can pull together other members of the Austin community,” he said. “I want to make sure that we don’t have one group speaking on behalf of Austin and Austin is like, ‘That’s not what we’re saying.’ That tends to be how we get things wrong.”

Deborah Williams, a longtime NAACP member and the organization’s former third-vice president, said the group is currently working on forging a coalition of 17 different agencies that will have a stake in the agreement.

“We want to be at the forefront of any investors coming into our area,” she said. “We want to make sure the homeowners and people living in this community have [priority] on land and foreclosed properties, so we can keep our people living in our community.”

[municipalities] around those code violations, so when we convey the property to a developer, at a minimum, what he knows is [he’s] got a tax-free, lien-free property that has been secured, cleaned out and maintained,” said Rob Rose, the land bank’s new executive director, during a recent informational meeting on the bank in suburban Maywood. Rose has also presented in Austin before the West Side NAACP.